The audio version of this article was first shared in Episode 48: A Bookchat about The Blackout Bookclub with Amy Lynn Green & a Review of Come Down Somewhere by Jennifer L. Wright

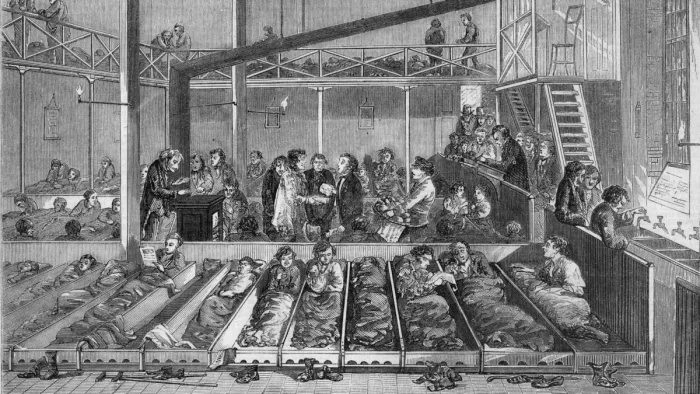

Anyone slightly familiar with British and American history has heard of the infamous poorhouse or workhouse. These municipal institutions generally provided the barest possible food and shelter to the elderly, disabled, and very poor, in exchange for whatever work the person could provide. They were designed to make poverty as unbearable as possible in an effort to keep people working rather than relying on the poorhouse.

Today we look at a few jobs people turned to as a last resort to keep themselves out of the poorhouse.

Slop Shop Sewing and Shoebinding

In the 1700’s in America, poor widows with young children couldn’t exactly leave their little rooms to go work. So clothing shops found a way to bring the work to them.

In port towns, sailors were constantly arriving in town and staying only a day or two, but they needed supplies and new clothing. They hadn’t the time or money for tailored clothes, so shops began selling ready-made “slops,” which was the term for the clothing sailors wore.

For extremely low pay, shops sent garment pieces to the widows, who worked 16-hour days every day sewing the pieces together. The garments were returned to the shops, finished up by a professional, and sold cheaply.

Shoes were done in a similar way. Leather pieces were cut and sent to the widows to be sewn together to make the shoes’ uppers, then a professional added the soles back at the shop.

The wage for both slop shop sewing and shoebinding was so low that most widows couldn’t really survive on their earnings. But it might keep them out of the poorhouse long enough for the children to reach earning age.

Scavenging

Children as young as four or five could be taught to scavenge, which was the eighteenth-century version of a recycling program.

Trash in the cities was dumped in the streets, often in large piles on the corners. Cats, dogs, and pigs that ran loose would root through the trash to find scraps of food.

People of all ages would sort through the refuse looking for things like scraps of cloth that could be sold to the paper-makers, bits of metal that a metalsmith would melt down to make tin soldiers, pieces of bone for the bakers, scraps of leather that a cobbler could patch together to make shoes for poor people.

So many things could be resold, and it earned a little something that might contribute to the family income or keep a person off the streets at night.

Baby Squirrel Collector

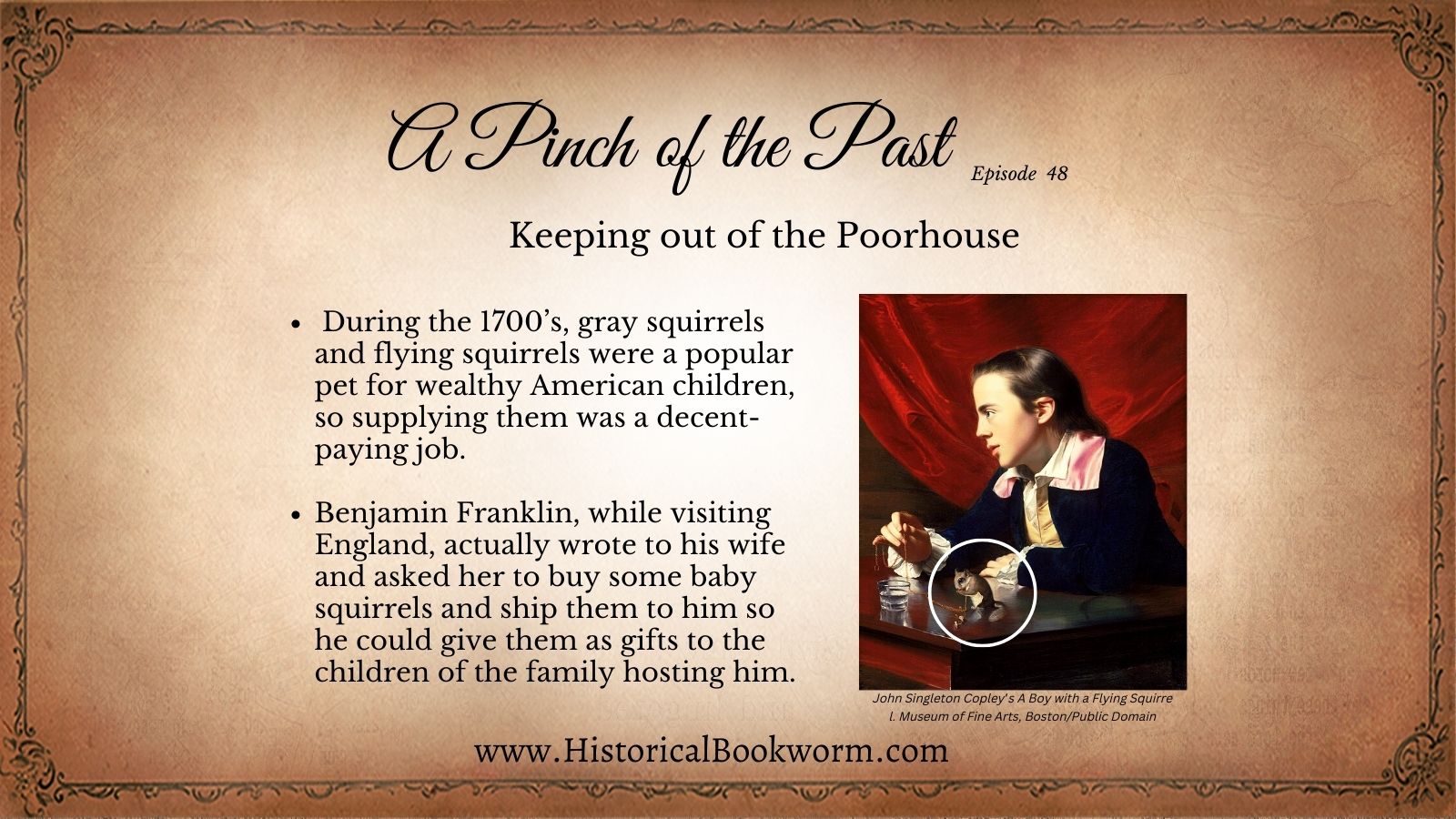

During the 1700’s, gray squirrels and flying squirrels were a popular pet for wealthy American children, so supplying them was a decent-paying job.

Boys and young men climbed trees in the woods and collected baby gray squirrels from their nests, then sold them in the marketplace.

Benjamin Franklin, while visiting England, actually wrote to his wife and asked her to buy some baby squirrels and ship them to him so he could give them as gifts to the children of the family hosting him.

Other than the fact that small teeth probably bit your fingers with some regularity, this job had just one drawback–it was seasonal. Twice a year you could collect baby squirrels, but the rest of the time, you’d need a fallback.

These three jobs just scratch the surface of the low-paying–and often disgusting–jobs people undertook to make ends meet. Kind of gives me a new appreciation for my less-than-exciting office job!

One Reply to “Keeping out of the Poorhouse”

Comments are closed.