The audio version of this article was first shared in Episode 47: A Bookchat about Caesar’s Lord with Bryan Litfin & a Review of Paint and Nectar by Ashley Clark

The practice of medicine is a fascinating–and sometimes disturbing–subject of history. Today we look at just a few weird practices people hoped would cure them of illness and injury.

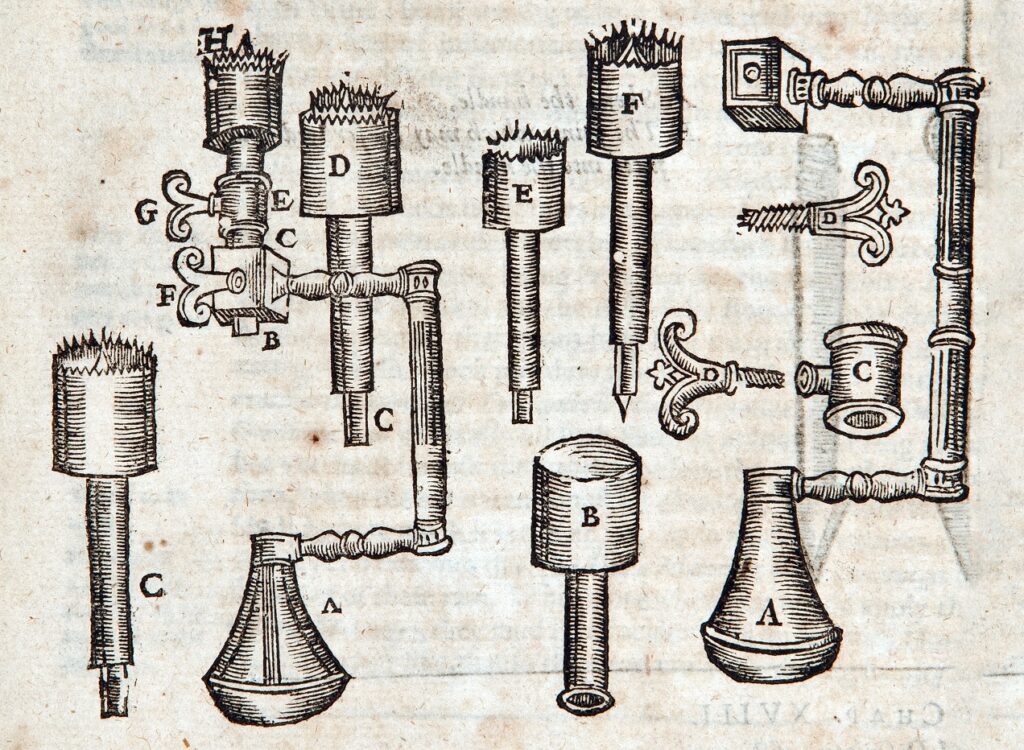

Trepanning

What would you imagine to be the surgery found earliest in the archeological record?

Dating back to prehistoric times, trepanning or trephination is the practice of boring or scraping holes in the human skull. Archeologists have found evidence of trepanning all over the world–China, South America, Europe–and in men, women, and children. While it sounds crude, it was actually a delicate process. Ideally, the surgeon bored only through the skull itself, exposing the tissue underneath but not actually cutting into the meninges or blood vessels surrounding the brain.

Roman writer Galen acknowledged the danger of the process, stating that too much pressure accidentally applied to the meninges would render the person unconscious or paralyzed.

In spite of the risks, trepanning was used to treat head trauma for thousands of years. It aided in removing bone fragments from a skull bashed by a weapon or a fall. It relieved the pressure of subdural bleeding. During the Middle Ages, it was a treatment for severe headaches and migraines, and even mental illness.

While we may wonder why people attempted this with only handheld iron or stone tools, the survival rate of patients was actually quite high, many healing and living years after the treatment. Some skulls found in France, dating back to approximately 6500 B.C., show patients who had the operation at some point, healed, and eventually underwent it again later in life.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Trephination/

Bubonic Plague

When the bubonic plague, or Black Death, swept Europe, many bizarre and sometimes horrifying treatments arose–none of which were successful. A bacterial infection that infects the lymph nodes, bubonic plague is treated with antibiotics today. In fourteenth century Europe, faced with a disease that could kill within 12-72 hours of the symptoms’ onset, one doctor wrote: “Instantaneous death occurs when the aerial spirit escaping from the eyes of the sick man strikes the healthy person standing near and looking at the sick.” They just had no clue how to prevent transmission or to treat their patients.

One treatment called for killing a snake and chopping it up in pieces. The poultice was then smeared over the swollen buboes or boils. The reasoning was that snakes were evil, and evil is drawn to evil. The evil in the snake was supposed to draw the evil disease out of the person’s body.

https://www.thecollector.com/the-black-death-medieval-cures/

https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/black-death

Unicorn Horn

Magical cure-alls were also popular medicine in medieval Europe. One such substance was the horn of a unicorn.

According to mythology, only a pure maiden could subdue a unicorn, so its horn–known as alicorn–was very rare and expensive.

Ground into powder and mixed into food or drink, alicorn was a reputable treatment for any illness–it was even tried for the Black Death.

While the existence of unicorns was accepted in ancient and medieval times, scholars today think the tusk of a narwhal or the horn of a rhinoceros may have been the actual source of alicorn.

Also: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unicorn_horn

Acupuncture

We finish with a practice still common today–acupuncture.

Originating in ancient China about 3000 years ago, the first thorough documentation of acupuncture comes from The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, a book from around 100 B.C. Acupuncture is based on the theory that a vital life force called Qi (chee) flows along pathways in the human body. The strategic piercing of the skin with very thin needles was thought to regulate and balance the flow of Qi.

While it sounds very mystical, the practice has undergone extensive research since 1950, and reputable studies have shown it has a positive effect on many patients. Most acupuncture practiced in the United States today is a combination of Eastern and Western research.

It stimulates nerves and muscles, and these days may include electric charges administered through the needles. Pediatric patients or those averse to needles may even opt for laser acupuncture, which has proven just as effective as the traditional treatment.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/acupuncture/about/pac-20392763

While we may laugh or shake our heads at what passed for medical treatment in history, all science is, after all, a process of experimentation. I can’t help wondering what accepted practice today will surprise the doctors in years to come.

One Reply to “Strange Medical Practices”

Comments are closed.